Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s Cello Concerto is inspired by the idea of teetering and balancing on the edge. Beethoven’s classic brings equilibrium and hope.

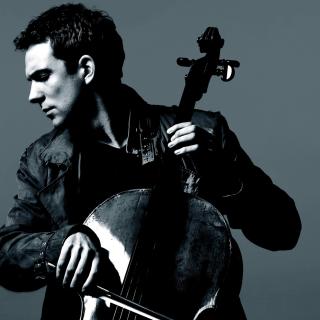

Thorvaldsdottir’s concerto features soloist Johannes Moser, renowned for his efforts to expand the reach of the classical genre, as well as his passionate focus on new music.

Beethoven's music has often accompanied major turning points in European history. The Seventh Symphony was performed in November 1989. Three days after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Berlin Philharmonic played it at a concert for East Germans. The concert was free; all you had to do was show your GDR identity card at the door of the Philharmonie. Already at four o’clock in the morning, a long line had formed around the concert hall.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Grosse Fuge Op. 133

If the symphonies of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) were showcases for his creative ideals, his string quartets were a laboratory for experimentation. His 16 quartets fall into three distinct stylistic periods; those completed after the Ninth Symphony really pushed the envelope of the Classical style. Conservative listeners of his time took them as conclusive proof that not only was Beethoven deaf, but he was also clearly out of his mind.

The Grosse Fuge Op. 133 began life as the finale of the String Quartet Op. 130 (1826), inflating the total duration of the work to more than 50 minutes. Its frosty reception spooked the publisher, who insisted that Beethoven provide a lighter finale for the quartet. The result was a contradance, carefree to the point of sarcasm. It remained Beethoven’s final completed work. The Grosse Fuge was published as a standalone piece two months after the composer’s death. Conductor Felix Weingartner arranged it for string orchestra in 1933.

The piece has been interpreted in wildly differing ways: some hear a parody of the Baroque form it emulates, while others hear an apocalyptic anticipation of death. Beethoven himself gave no indication either way. The fugue has been the most distinguished vehicle for demonstrating compositional skill ever since the Baroque era, and Beethoven often used the form as a culminating device in his works. Yet the Grosse Fuge dwarfs all his previous efforts in the genre — and its subtitle “at times free, at times learned” implies that the old rules have been broken and there is no going back.

Jaani Länsiö, translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

Anna Thorvaldsdottir: Before we fall

Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir (b. 1977), Composer-in-Residence of the Helsinki Philharmonic, is one of the most original orchestral composers of our time. Her music distantly echoes the field music of György Ligeti, where a mass of notes blend into a vast entity that flows and shifts shape gradually. Thorvaldsdottir’s music always tells a story — not literally, but through impressions prompted by concepts and work titles that shape the drama that unfolds.

Before we fall was premiered in San Francisco in May 2025. It was jointly commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony, the BBC Proms, the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and the Odense Symphony Orchestra, and it is Thorvaldsdottir’s first concerto. The cello is her own instrument, and she wrote this piece specifically for Johannes Moser. The work avoids virtuoso writing for its own sake, even if the solo part is quite conspicuously a virtuoso vehicle. “Of course, it’s always about the music and how the music sounds, and that kind of grows internally,” Thorvaldsdottir explains. “But it’s impossible not to think about think about fingerings and how it is in the hand, so of course that manifests as well.”

True to its title, Before we fall lurches from one side of the abyss to another, both in individual moments and in its overall arc. A harmony underlay establishes a balance that the cello defies, both alone and in close cooperation with the orchestra.

Jaani Länsiö, translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony no. 7 in A major Op. 92

The odd-numbered symphonies of Ludwig van Beethoven can be seen as a ‘Napoleon cycle’. The Third and Fifth are about an individual’s struggle leading to victory or destruction, while the Ninth culminates in a celebration of the unity of peoples, the Ode to Joy. The Seventh Symphony (1812) is quite concretely linked to the Napoleonic Wars, having been premiered in Vienna at a benefit concert for soldiers injured at the Battle of Hanau.

Having said that, the Seventh Symphony is almost completely devoid of melancholy — on the contrary, it is ecstatic, dancing and vibrant. It is no coincidence that Beethoven was concurrently writing arrangements of Scottish and Irish folk dances for a British publisher. Indeed, the finale incorporates a version of an Irish folk song, Save me from the Grave and Wise. The work was an instant success, even if composer Carl Maria von Weber considered it the “delusions of a madman” and pianist Friedrich Wieck suspected that its creative process had been fuelled by copious drinking. Beethoven himself regarded the Seventh as his best symphony.

The four-movement work opens with an extensive introduction whose tense harmonies and staccato scales eventually lead to A major and the ‘Vivace’ main section. Its main subject, presented on the flutes, becomes the backbone of the entire work. The ‘Allegretto’ resembles a funeral march and is one of Beethoven’s best-known symphonic movements. The third movement, ‘Presto — Assai meno presto’ is a mercurial scherzo, and the finale steps up the energy in a joyful and liberating dance.

Jaani Länsiö, translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, has established himself as one of the outstanding conductors of his generation. Born in Finland in 1956, he began his career as a violinist. Today, he is renowned as an artist of exceptional versatility and breadth.

Saraste has previously held principal conductorships at the WDR Symphony Orchestra in Cologne, the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and has served as Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. As a guest conductor, he appears with major orchestras worldwide, including the Orchestre de Paris, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Staatskapelle Berlin, the Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Symphony Orchestras of Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco.

Coaching and mentoring young musicians is of great importance to Saraste. He is a founding member of the LEAD! Foundation, a mentorship programme for young conductors and soloists.

www.jukkapekkasaraste.com

Johannes Moser

Johannes Moser (b. 1979) is renowned for his efforts to expand the reach of the classical genre, as well as his passionate focus on new music. Moser has performed with the world’s leading orchestras such as the Berliner Philharmoniker, New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, BBC Philharmonic at the Proms, London Symphony, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest, Tokyo NHK Symphony, and Cleveland Orchestra with conductors of the highest level including Zubin Mehta, Pierre Boulez, Paavo Järvi, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, and Gustavo Dudamel.

Born into a musical family in 1979, Johannes began studying the cello at the age of eight and became a student of Professor David Geringas in 1997. He was the top prize winner at the 2002 Tchaikovsky Competition. In 2014 he was awarded with the prestigious Brahms prize.

His recordings include the concertos by Dvořák, Lalo, Elgar, Lutosławski, Dutilleux, Tchaikovsky, Thomas Olesen and Fabrice Bollon. Moser plays on an Andrea Guarneri Cello from 1694.

Timo Kalliokoski

On the stage today

Violin 1

Kreeta-Julia Heikkilä

Tami Pohjola

Pekka Kauppinen

Katariina Jämsä

Helmi Kuusi

Ilkka Lehtonen

Jani Lehtonen

Petri Päivärinne

Kalinka Pirinen

Satu Savioja

Elina Viitasaari

Dhyani Gylling

Alexis Mauritz

Harry Rayner

Violin 2

Anna-Leena Haikola

Teija Kivinen

Kamran Omarli

Serguei Gonzalez Pavlova

Matilda Haavisto

Linda Hedlund

Sirkku Helin

Liam Mansfield

Krista Rosenberg

Ángeles Salas Salas

Virpi Taskila

David Seixas

Viola

Atte Kilpeläinen

Torsten Tiebout

Petteri Poijärvi

Aulikki Haahti-Turunen

Kaarina Ikonen

Liisa Orava

Iiro Rajakoski

Mariette Reefman

Laura Világi

Tuukka Susiluoto

Cello

Lauri Kankkunen

Tuomas Ylinen

Beata Antikainen

Mathias Hortling

Veli-Matti Iljin

Fransien Paananen

Ilmo Saaristo

Mikko Ivars

Bass

Ville Väätäinen

Eero Ignatius

Paul Aksman

Henri Dunderfelt

Taavi Korhonen

Joonas Korjus | Flute

Niamh McKenna

Elina Raijas

Päivi Korhonen

Oboe

Nils Rõõmussaar

Simeon Overbeck

Clarinet

Samuel Buron-Mousseau

Anna-Maija Korsimaa

Heikki Nikula

Bassoon

Jussi Särkkä

Alan Davidson

Noora Van Dok

Horn

Ruben Buils Garcia

Mika Paajanen

Sam Parkkonen

Joonas Seppelin

Trumpet

Obin Meurin

Mika Tuomisalo

Trombone

Victor Álvarez Alegria

Valtteri Malmivirta

Tuba

Ilkka Marttila

Timpani

Tomi Wikström

Percussion

Tuomas Siddall

Pasi Suomalainen |