From scrap paper to legible notation

The “HUOM! – History’s Unheard Orchestra Music” project aims to bring to light and “rediscover orchestra material that has been stored in various archives. This may sound straightforward – simply put the sheet music on a music stand and let the musicians start playing. In fact, however, using old sheet music involves a wide range of challenges.

In general, a composition is thought to take three different forms: the work heard inside the composer's head, its notation or manuscript, and finally the performed version, which is realised from the sheet music. The composer writes a manuscript for the work, in the case of orchestral works we speak of a score, which are like the blueprints of the work. From the score, parts are taken for each musician. In this way, a flutist sees only what they need to play, as does a violinist and so on. The conductor is the only one with sheet music for the entire orchestra in front of them.

In the past, sheet music was written entirely by hand. In cases of urgency, or a lack of resources, the composer’s original manuscript was used by the conductor, and it may well have been that the composer had also written the parts for the musicians the night before the premiere. In more fortunate cases, a copyist could clean up the manuscript and the parts. However, the quality of these handwritten sheets in no matches that of notes engraved and printed in a printing press.

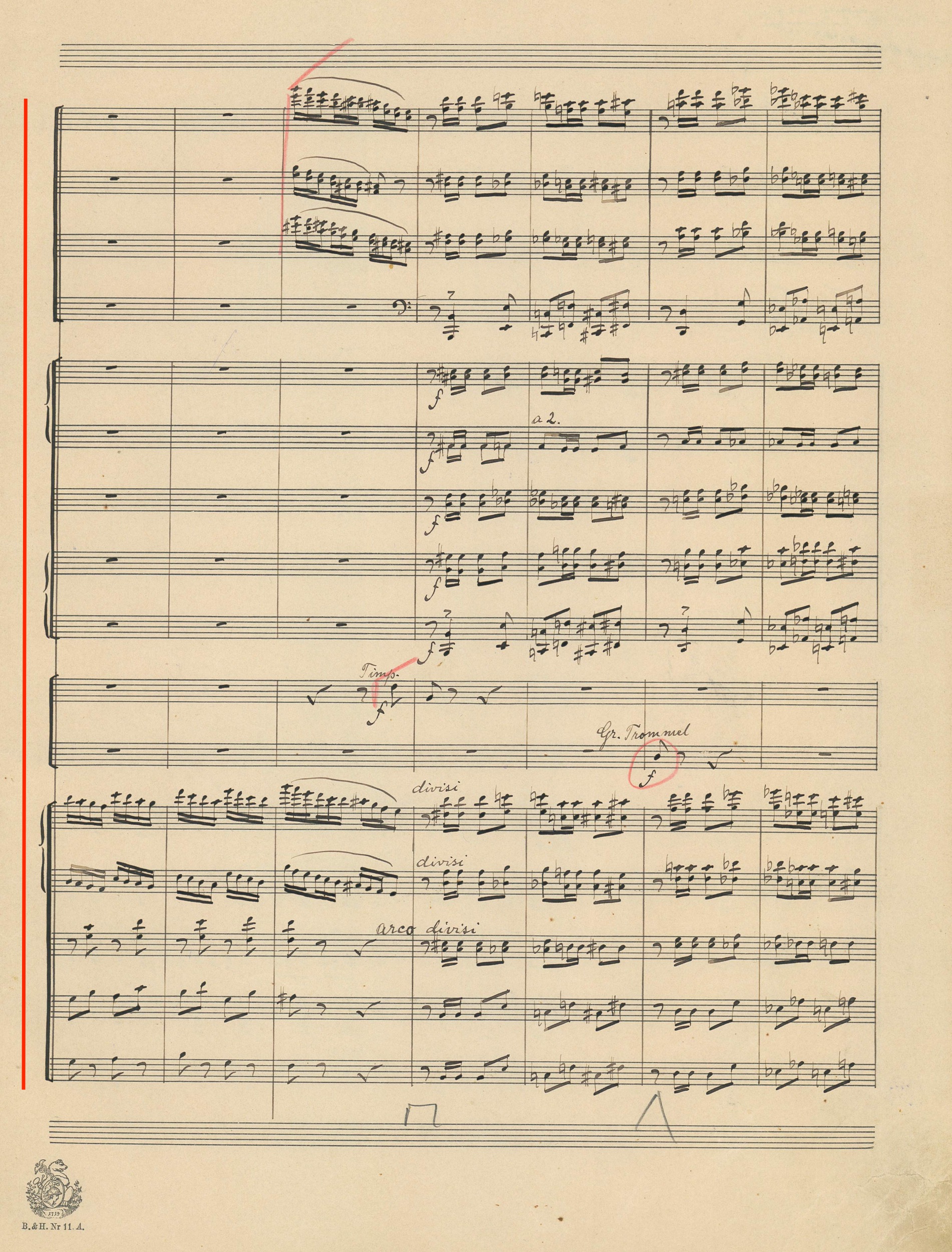

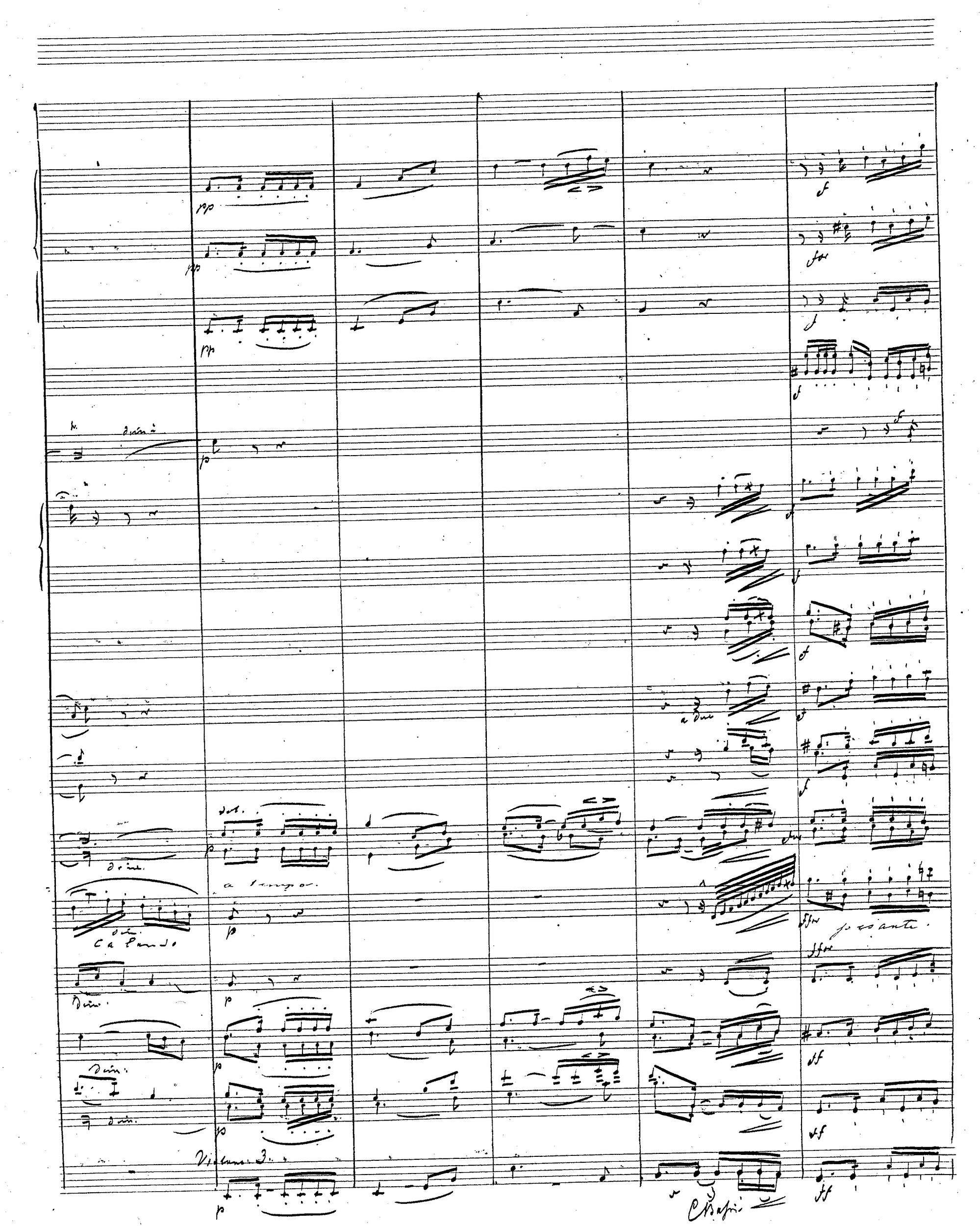

Most of the works in the HUOM! project were either written in the hand of the composer or a copyist. This poses challenges for both the conductor and the musicians. The manuscript may in some cases be sketchy, or it may have gone through several rounds of correction that appear as an intense jungle of ink and coloured markings. Individual parts can also be calligraphically beautiful pencil drawings with their decorative strikethroughs and inserts yet extremely challenging to read and play.

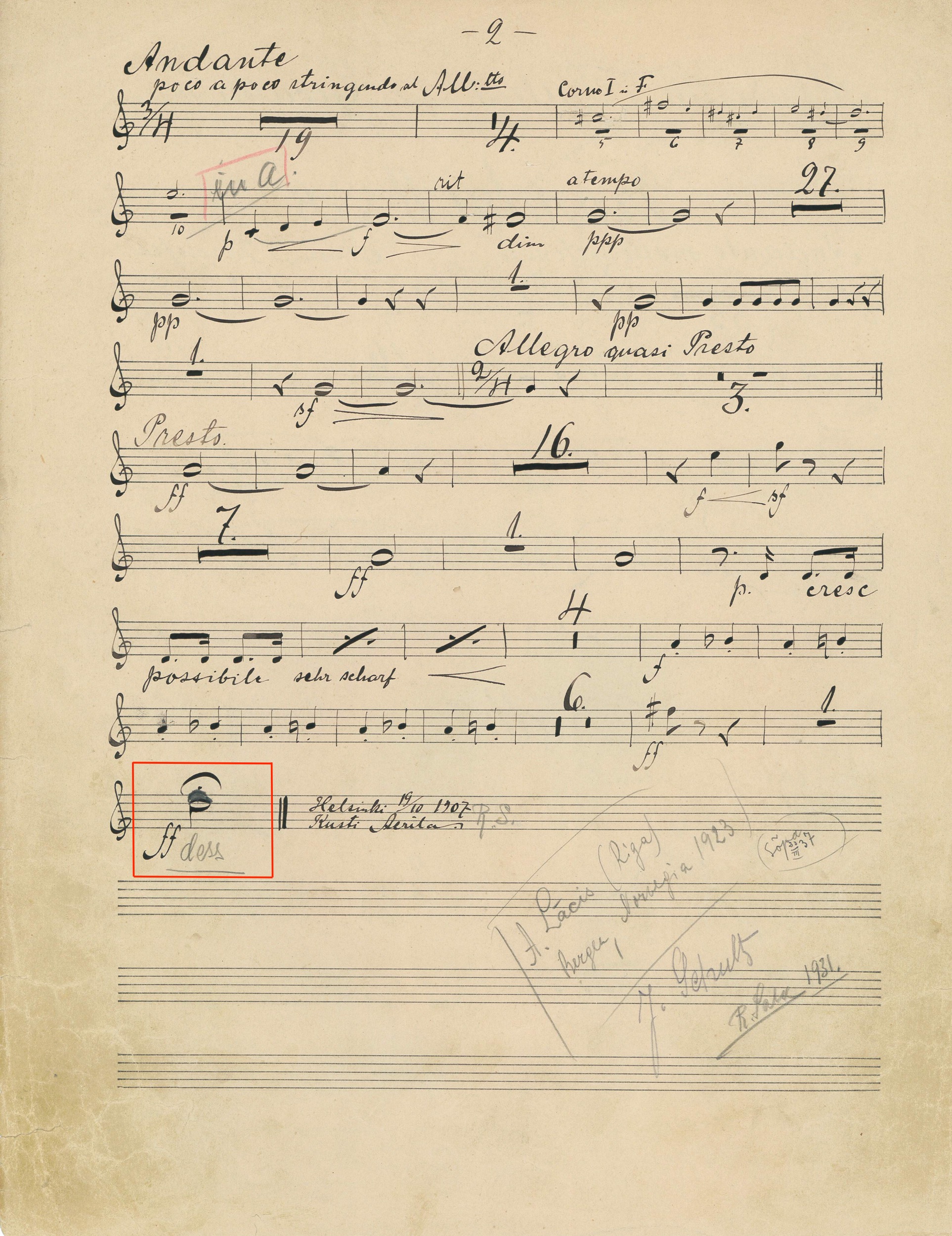

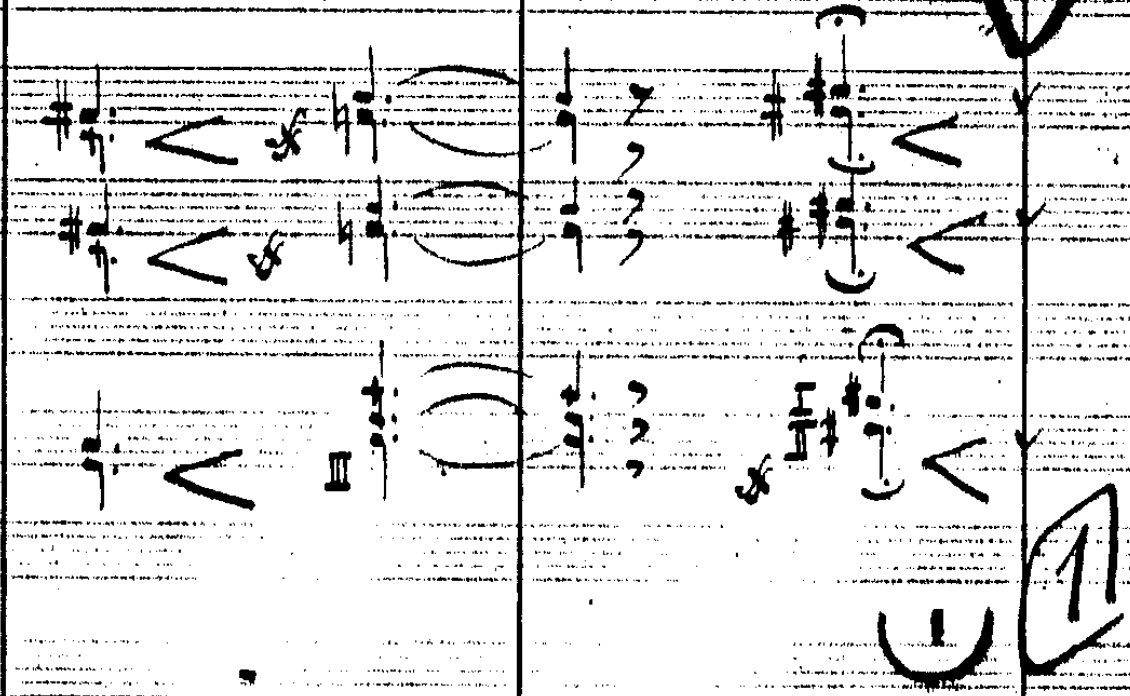

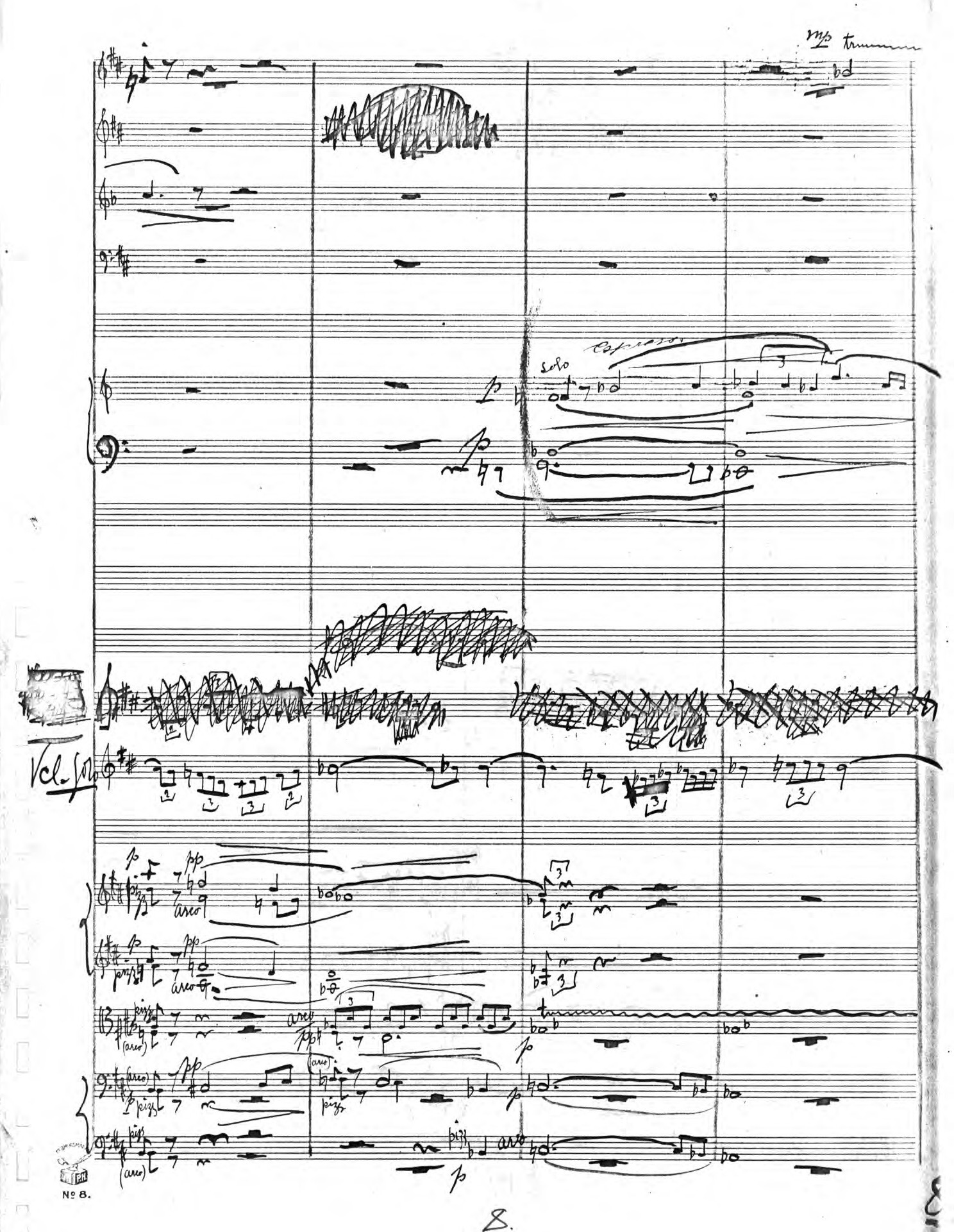

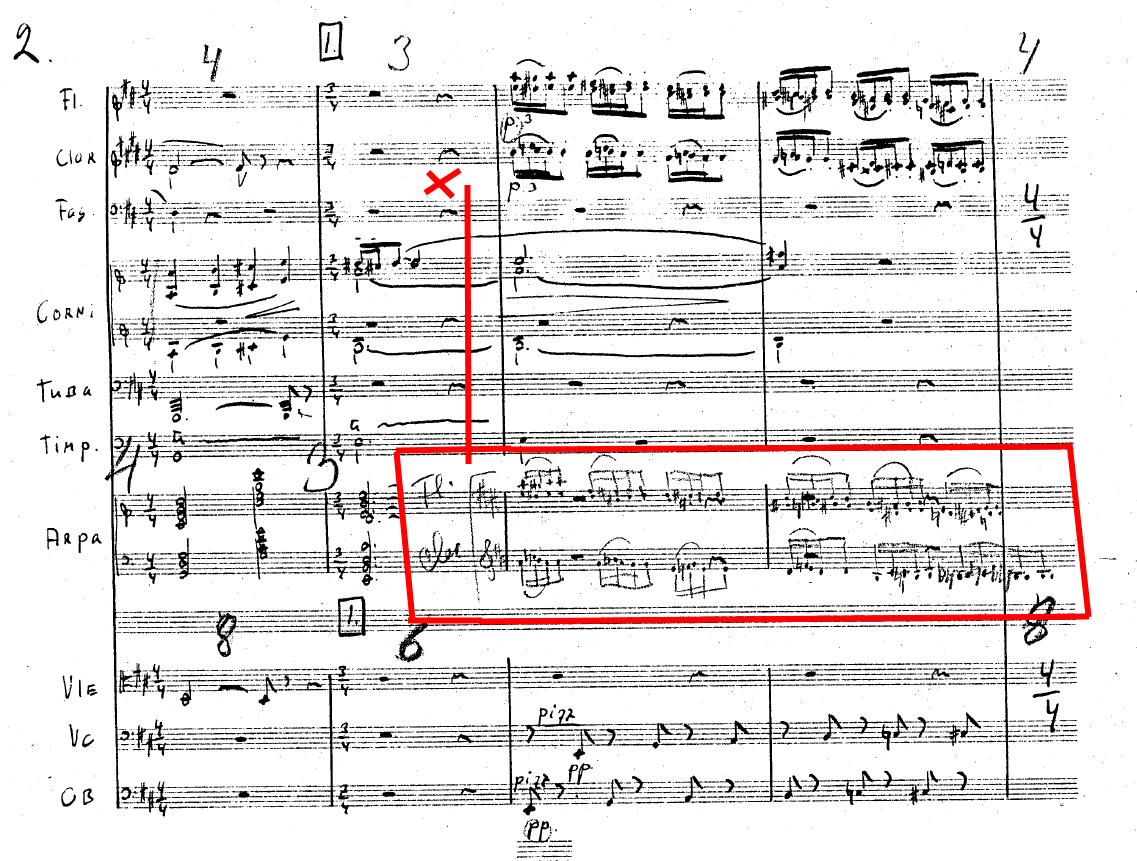

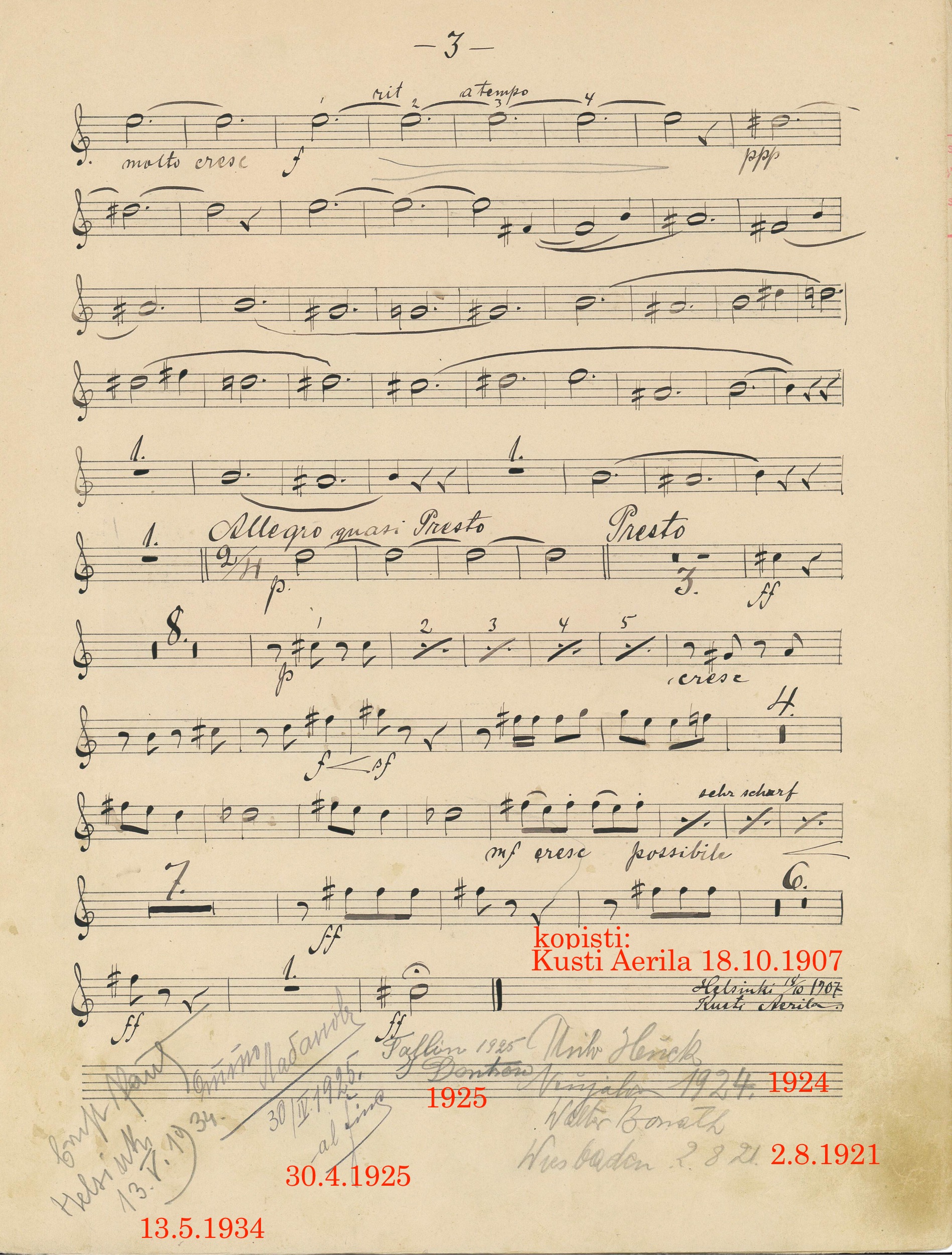

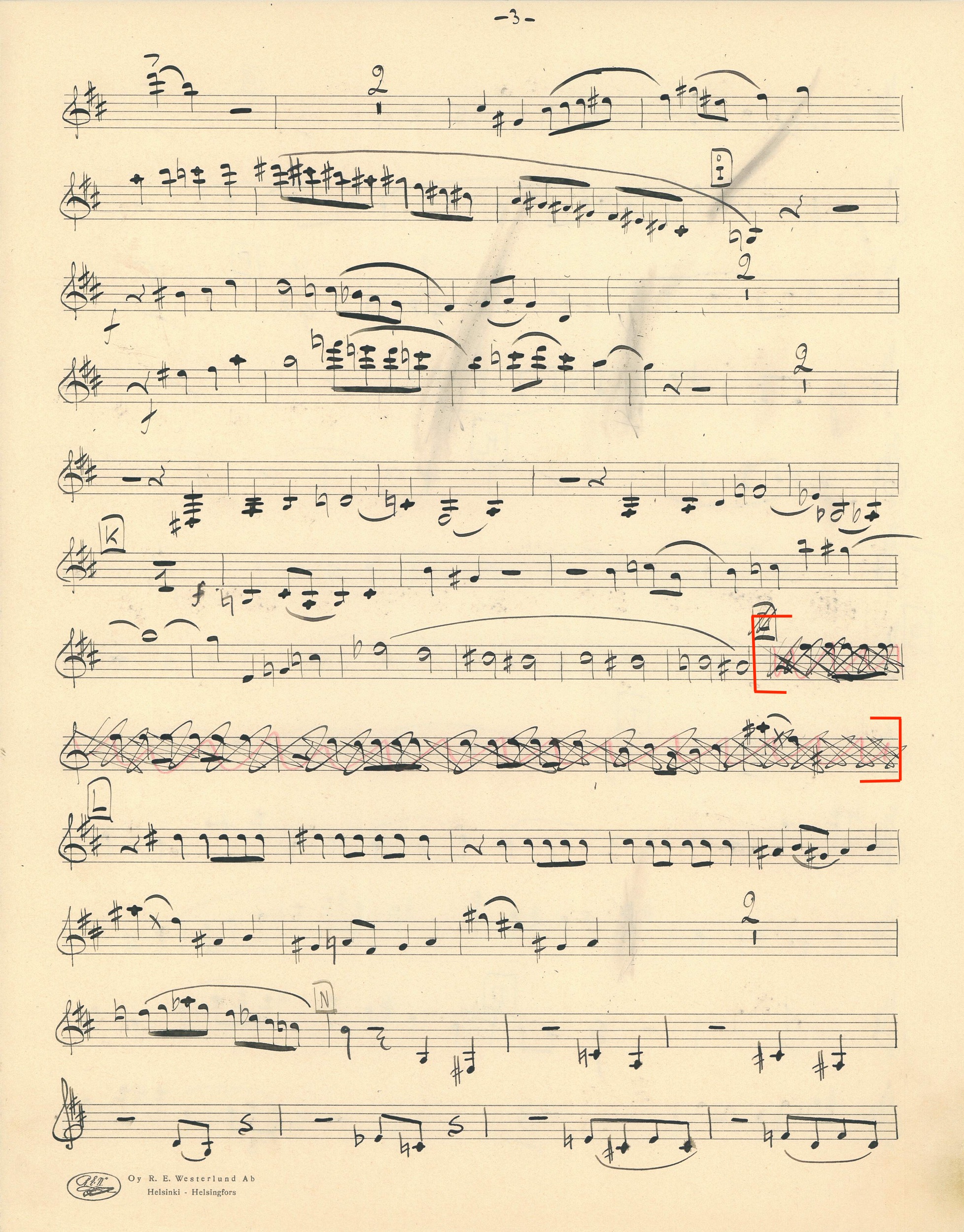

A picture says more than a thousand words - examples of the situations described above

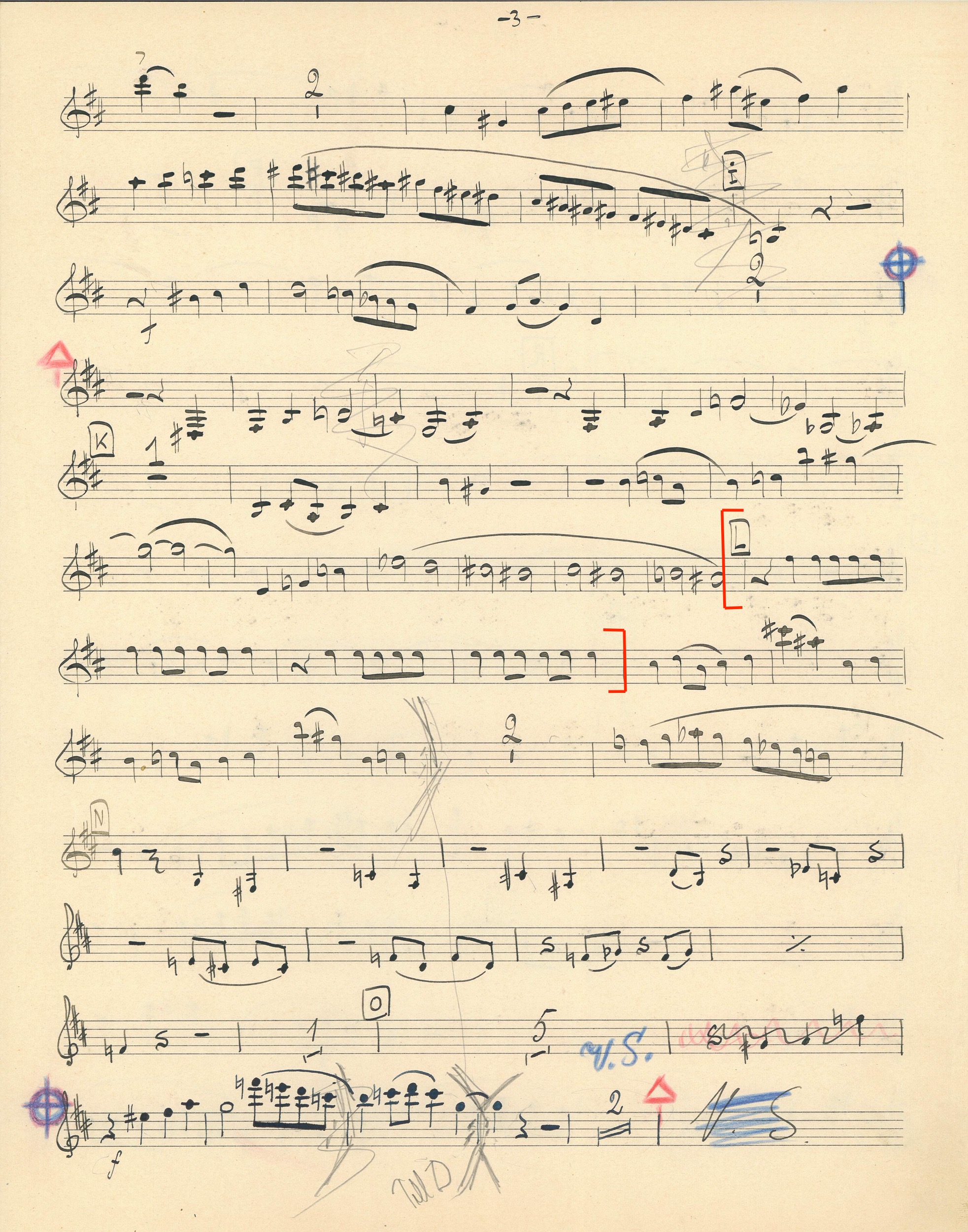

IMAGE 0 (above): A part written in ink. The last note (inside the red box in the picture) is unclear, as the pitch has been corrected in pencil and yet another correction is written below. Regardless, the overall appearance is beautiful and pleasing to the eye. Musicians of a younger generation in particular are accustomed to printed sheet music, however, and it is difficult for them to read handwritten sheet music.

IMAGE 1 (below): A low-quality archive copy with the lines of the staff faded. In such cases, it is preferrable to use colour facsimile copies of the original manuscript.

IMAGES 2 AND 3 (above): Deleted markings and unclear pen work.

When notes are cleaned up for the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, the work most often starts with the score, if it exists. The contents of the score are transferred to the notation software note by note, musical symbol by musical symbol. At this point already, certain inconsistencies are often revealed, such as missing markings. The composer may have resorted to shortcuts and shorthand if working in a hurry. The absence and possible addition of such markings is weighed in their musical context and a decision is made as to whether to add or omit. If omitted, questions may arise during the rehearsal phase: why does the first oboe play legato while the notes played by the second oboe are more articulated? If an addition is made, it is clearly marked as such so that the conductor is aware of the change and may, if necessary, request the musician not to heed the addition.

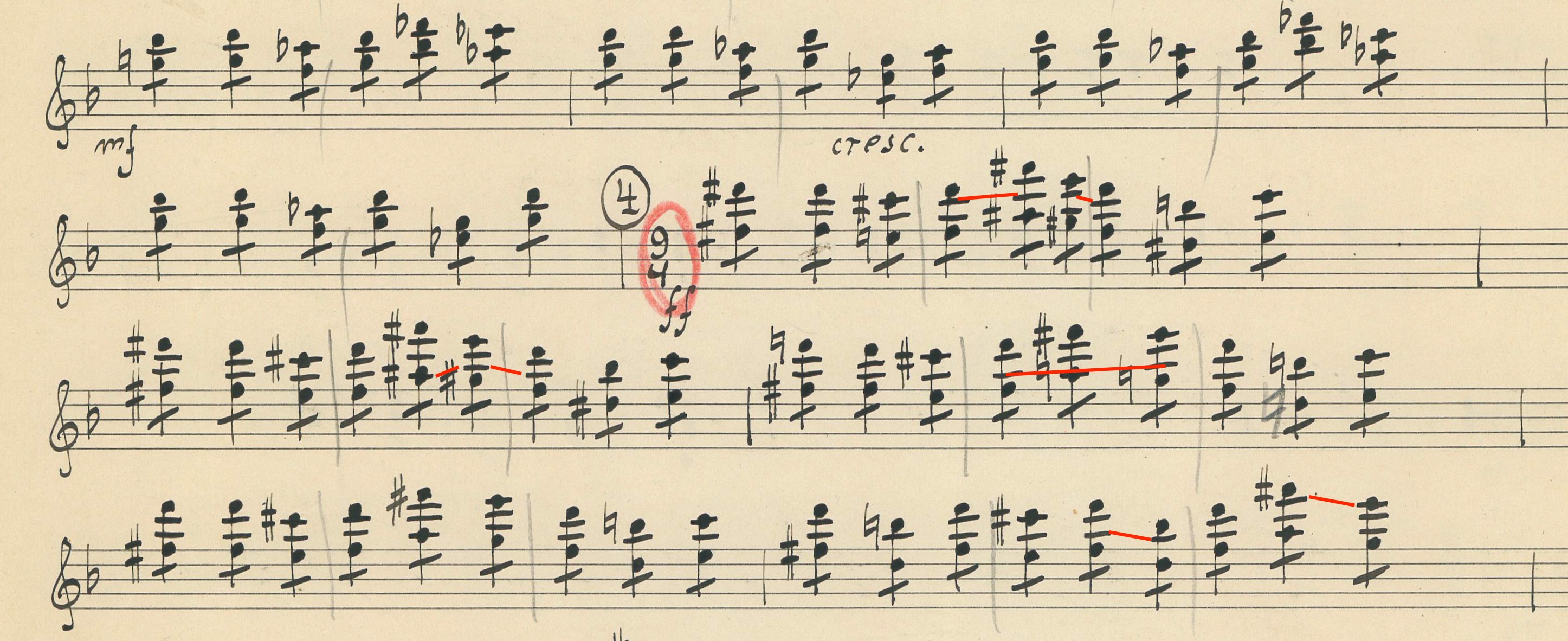

IMAGE 4: Markings for notes that have been cleaned up: the dotted slur and brackets indicate to the conductor that additions have been made.

IMAGE 5: Content that has been subsequently added to the manuscript and requires closer inspection determine whether it should be included.

Other challenges may include, for example, the key: the composer may forget to mark the key signature while composing in a certain key. This can lead to discordant harmonies and confusion. Clefs may also be mixed up or left out. This is especially true if the composer does not write a clef at the top of each page and can result in some truly remarkable and unexpected sounds.

IMAGES 6 and 7: The names of the instruments, clefs and key signatures have been excluded at the start of the next spread. Problems can be caused if the order of instruments changes unexpectedly.

Technical markings too are often rudimentarily drawn: does the pizzicato of the strings continue, even if the symbol refers to notes played on the bow of the instrument? Resolving these issues requires experimenting and drawing in some cases easy conclusions. Another challenge is posed by transposing wind instruments. A score can be written in the key of C, so that the notes of all the instruments can be read directly in relation to each other. However, when writing a transposed score, it is written as it appears when matched to the key of the instrument itself. A-tuned clarinets and F-tuned trumpets, not to mention English horns, can sometimes end up being written “correctly but in the wrong key”. This can result in unintended sounds, strange harmonies and more experimenting.

IMAGE 8 (above): French horn parts in particular can often be determined by looking at the performance history of the piece. In this case, copyist Kusti Aerila has written the part on 18 October 1907, and the piece was performed several times in the 1920s and once in spring 1934.

Despite years of training, composers may sometimes forget what they have learned in their instrument studies and compose music that cannot actually be played by the instrument in question. The notes can be too low or too high or otherwise simply impossible to play. This too can lead to confusion and require further examination of the surrounding music to find a workable solution.

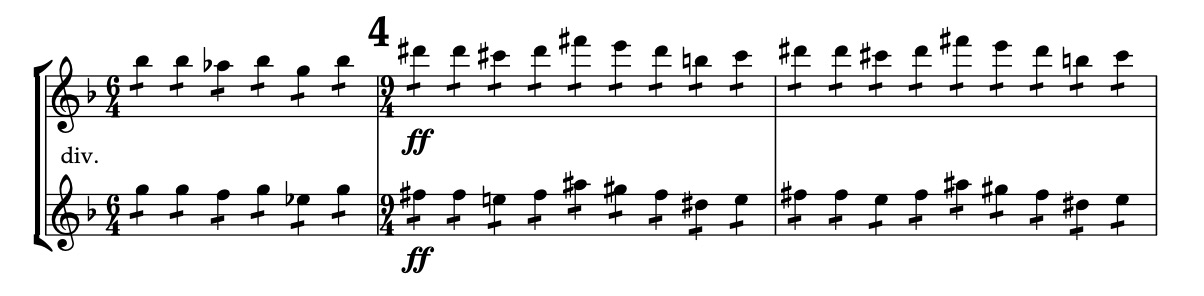

IMAGES 9 and 10 (below): The copyist’s eyes have strayed and some of the notes for the first clarinet (right) have been written for the second clarinet (left). The section in question is marked in red.

Once the score has been transferred to the notation software, the music can be checked by listening to it electronically. The latest software can simulate the instruments of a symphony orchestra and play the piece with relatively acceptable quality for getting a general idea about the accuracy of the notation. The most important aspect when listening at this stage, however, is to hear any wrong notes with your own ears. If the piece has harmonically traditional, any wrong notes will be heard immediately so the mistake can be duly rectified. Otherwise, this work will have to be done during rehearsals, which takes up the time of the entire orchestra.

Notes written with an ink pen or otherwise rapidly in a frenzy of inspiration may be too big and appear to cover several notes on the paper. In these cases, the overall harmony in the bar is examined to reach a conclusion about the intended tone. In general, the person cleaning up or editing the notation engages in an internal dialogue with the sheet music and seeks to find solutions to the points in question that best suit the composer’s intended purpose.

IMAGE 11: When written in ink, the markings inevitably become slightly thicker. Ledger lines in particular are usually problematic, especially if there are a lot of them. In this example, the ledger lines are not level, which is quite typical and makes reading the notes difficult. The varying heights of the ledger lines are marked with a red line.

IMAGES 12 and 13: The section in Image 11 looks like this when rewritten on computer (Image 12). In Image 13, overlapping notes are separated onto their own staffs to make them easier to read. A mistake was found in the original notes when recopying them: a natural had been replaced by a flat (marked by a red arrow).

It can also happen that the score and parts found in the archive do not correspond. There can be numerous reasons for this, for example if one generation of the score has disappeared, or the parts have been written at a different time from the score, in which case the composer may have had different thoughts about the overall composition. In these cases, a decision has to be made as to which one to follow: the score or the individual parts. If it is likely that the score has been written in the hand of the composer, then the original score is used. This is referred to as the definitive version (Fassung letzter Hand) as most accurately representing the composer’s original thoughts, since it was written in his or her own hand.

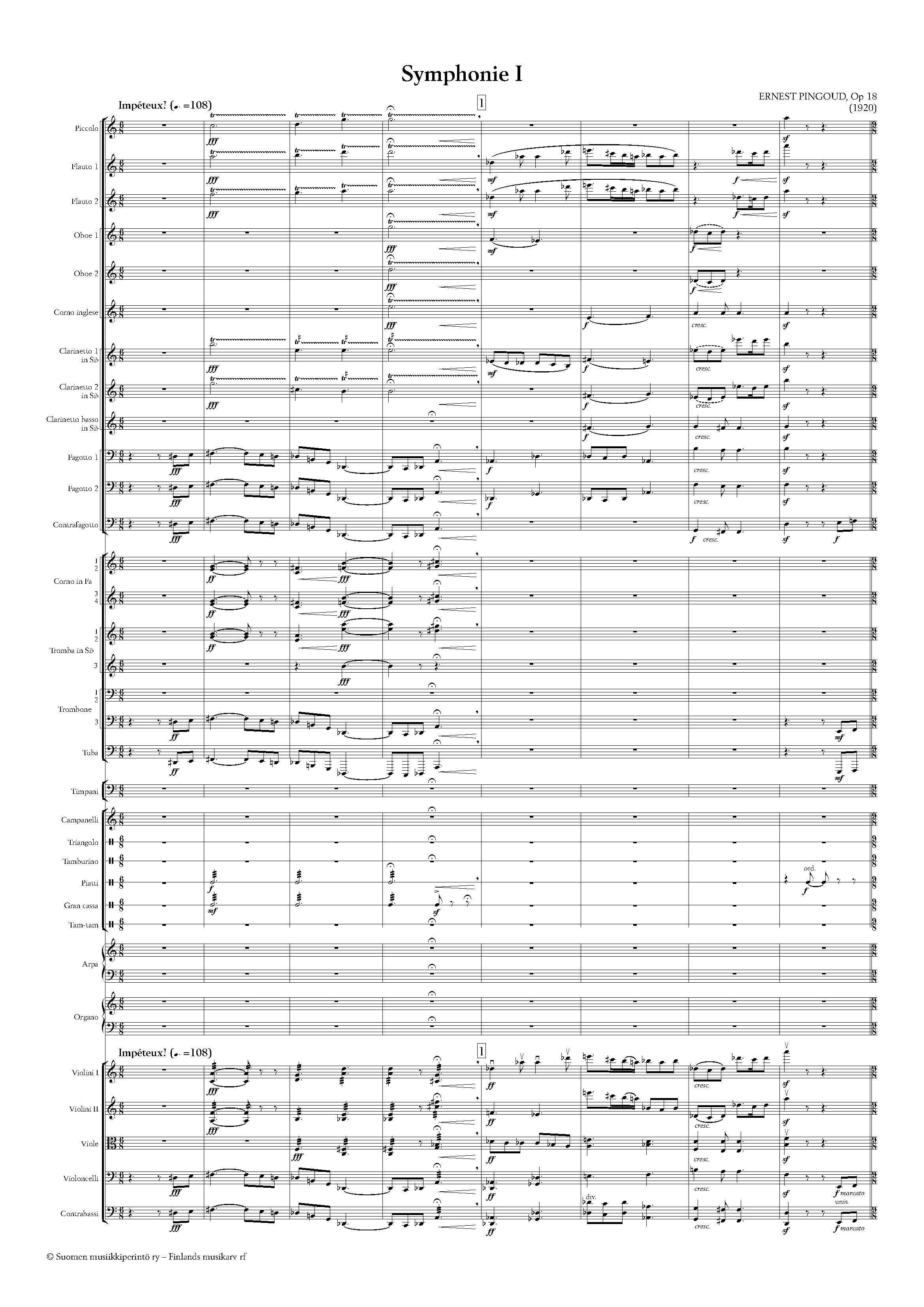

After all of these challenges have been addressed and resolved, the notes are finally ready to be performed by the orchestra in concert, as in this final example:

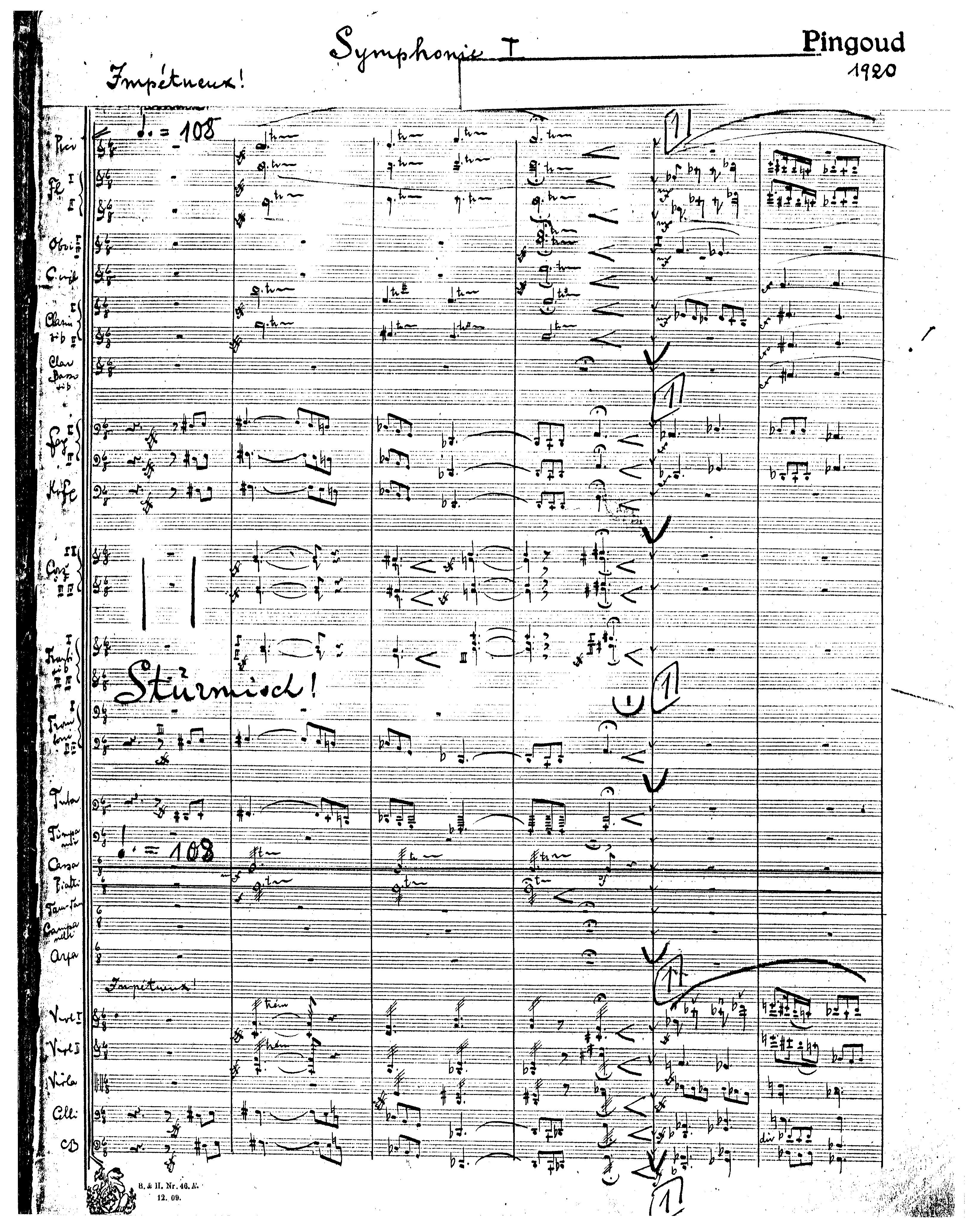

IMAGE 14: First page of the handwritten score

IMAGE 15: First page of the score after it has been cleaned up and recopied on computer.

Author: Jari Eskola

Translation: Edward Crockford

IMAGE SOURCES:

Images 0, 6, 8: Notes of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra

Images 1-3, 7, 14: Music Finland

Images 4, 12-13: Author

Images 5, 9-11: Fennica Gehrman Oy

Image 15: Finnish Musical Heritage Society