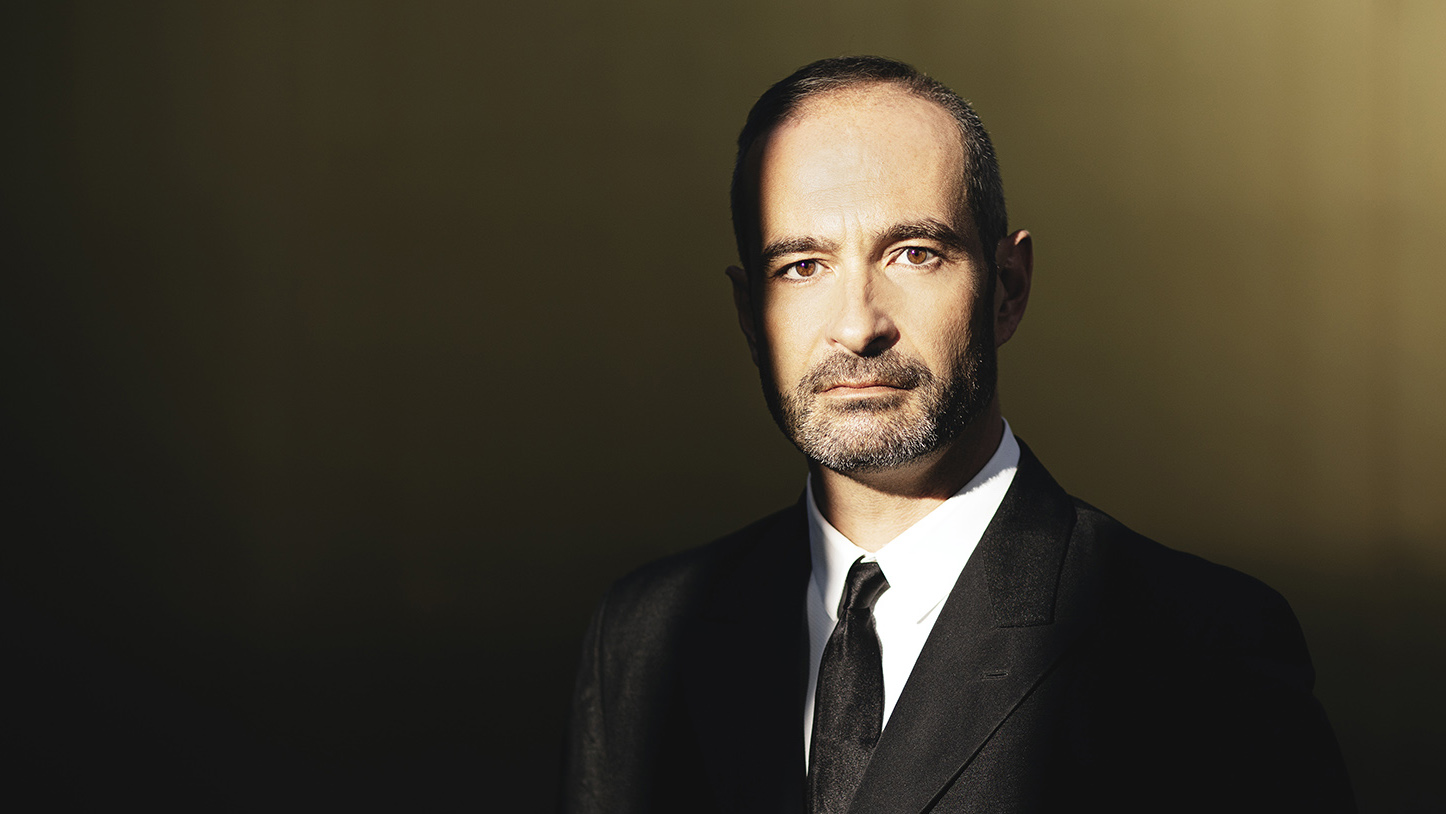

Antonello Manacorda's long-awaited return to Helsinki leads the audience and the orchestra into the mysterious triangle of the concert experience.

“The audience is always part of the performance. It is a mysterious triangle: composer, musicians, and audience. One hears the audience. Their impact is most powerfully felt in their silence.” (classicalvoice.org) Conductor Antonello Manacorda's long-awaited return to Helsinki leads the audience and the orchestra into the mysterious triangle of the concert experience. Manacorda and Robert Schumann are our celebrated guests for two weeks!

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 4

Having devoted the 1830s almost entirely to music for the piano, Robert Schumann (1809–1856) then turned his manic attention first to songs and then symphonies. His first symphony, written in a mere few weeks, was a great success and encouraged him to believe that writing a symphony was child’s play. His second, clearly influenced by Beethoven’s fifth, soon proved him wrong, however. Its premiere was a disaster, it got banished from sight and would be left to gather dust for the next ten years. It then reappeared in 1851, its errors corrected and with lighter instrumentation under the title of Symphony No. 4 in D Minor, Op. 120.

In writing a symphony with movements linked together without a break, Schumann took symphonic unity further than any of his predecessors had done. Whereas Berlioz, for example, in his Symphonie fantastique, kept coming back to his theme either as such or with only minor changes, Schumann in practice based the whole of his D-minor symphony on a single motif first heard in the slow introduction to the first movement. The result was a homogeneous work in a single movement abounding in familiar melodies.

Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Rhenish, Op. 97

The Rhenish Symphony by Robert Schumann (1810–1856) is a combination of romantic licence and classical form: the rhythms and melodies are allowed to go their own ways, but within a very strict framework. Instead of the usual four movements, this symphony has five; Schumann was possibly inspired here by the example of Beethoven’s Pastoral, which also has five. Both works also reflect the images conjured up in their composers’ minds by nature and certain landscapes. The second movement of the Rhenish, a Ländler dance with a gently rocking theme, was originally titled Morning on the Rhine.

Schumann had been impressed by the Rhine since taking up the post of director of music in the city of Düsseldorf in autumn 1850 and a visit soon after to another city on the river, Cologne. Sadly, he nevertheless soon began to suffer from depression and tried to commit suicide by drowning himself in the river. Though rescued on that occasion, he died in a mental asylum two years later.

Violin 1 Pekka Kauppinen

Jan Söderblom

Kreeta-Julia Heikkilä

Katariina Jämsä

Helmi Kuusi

Elina Lehto

Jani Lehtonen

Kalinka Pirinen

Satu Savioja

Elina Viitasaari

Serguei Gonzalez Pavlova

Neea-Noora Piispa

Violin 2

Anna-Leena Haikola

Kamran Omarli

Teija Kivinen

Heini Eklund

Teppo Ali-Mattila

Sanna Kokko

Virpi Taskila

Mathieu Garguillo

Venla Saavalainen

Aimar Tobalina

Viola

Torsten Tiebout

Lotta Poijärvi

Ulla Knuuttila

Carmen Moggach

Hajnalka Standi-Pulakka

Remi Moingeon

Hanna Semper

Laura Világi

Cello

Lauri Kankkunen

Beata Antikainen

Basile Ausländer

Mathias Hortling

Aslihan Gencgonül

Hans Schröck

Bass

Adrian Rigopulos

Tuomo Matero

Eero Ignatius

Tomi Laitamäki | Flute

Elina Raijas

Jenny Villanen

Oboe

Hannu Perttilä

Nils Rõõmussaar

Paula Malmivaara

Clarinet

Osmo Linkola

Harri Mäki

Bassoon

Mikko-Pekka Svala

Noora Van Dok

Horn

Mika Paajanen

Miska Miettunen

Jonathan Nikkinen

Sam Parkkonen

Trumpet

Pasi Pirinen

Mika Tuomisalo

Trombone

Valtteri Malmivirta

Anu Fagerström

Joni Taskinen

Timpani

Tomi Wikström |